- ARPDAUPosted 13 years ago

- What’s an impressive conversion rate? And other stats updatesPosted 13 years ago

- Your quick guide to metricsPosted 13 years ago

ARM yourself: Keeping your customers is the secret to success

This is the third post in a series I’m calling ARM yourself.

Once you’ve acquired customers, you ought to keep them, right?

It’s amazing how many games companies don’t think like this. How much effort they put into getting customers through the door, and how little they put on keeping them when they arrive.

Actually, when you think about it, it’s not amazing at all. Games companies have never cared about satisfying their customers.

The traditional marketing model for the games industry has put zero thought into satisfying customers. Literally zero.

AAA publishing is about the release day. The CFO of a major games publisher once told me that he could predict the lifetime sales of a game, down to the nearest ten thousand units or less, based purely on day one sales. No wonder AAA marketing is focused so intently on initial launch, and has no interest at all about what happens after that.

This isn’t surprising either. When the business model consists of charging a user £40 for a game, with no recurring revenue, it really doesn’t matter if the user hates the game. You’ve already got their money.

We’re not in KAAAnsas any more, Toto

We’re not focused on AAA games any more. If you are reading this, you are interested in self-publishing, or web games, or Internet business in general. Unlike traditional games publishers, we care about our customers.

(Even AAA games aren’t like that anymore. Keeping users interested means you can sell them more DLC, or just stop them from trading the game in at a retail store.)

We also care, for commercial reasons, about making sure that they keep coming back. I’ve already written about the changing nature of game design, moving from “one more go” to “come back tomorrow” (and more about that in the Monetisation post). In this post, I want to talk about Retention.

Why does Retention matter?

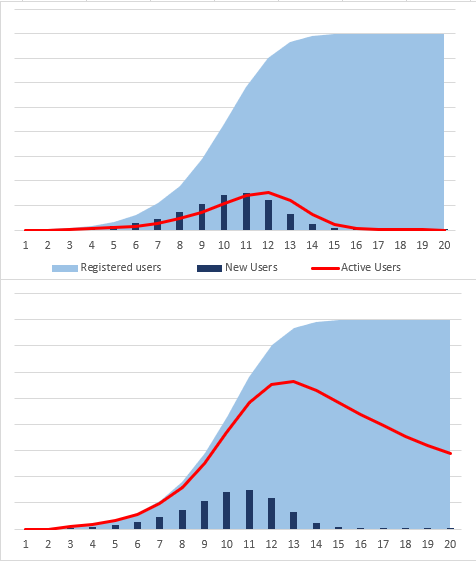

Retention matters because customer acquisition costs are going up. To compete, you need to either outspend customers on marketing, or get smarter at making the customers that you do get stay with you longer and become more profitable.

The great news for game designers is that Retention is at the core of what you do. Retention is about giving players good reasons to want to keep coming back to your game. And you want to do that anyway, right?

What follows are some examples of games that have used a variety of gameplay mechanics to encourage retention. Note that this is not an exhaustive list, and I’d like you to think of them as firelighters to ignite your design imagination, not as a template to follow.

Most of these examples come from social games, where the need to drive Daily Active Users is well understood. As I’ll discuss in a later post, the ARM yourself framework applies to many games and many situations, but is often most easy to explain in the context of Facebook games.

Daily rewards

The simplest mechanism is to give people an opportunity to get a daily bonus simply for turning up. Bejewelled Blitz does this by offering a one-armed bandit that you spin to win bonus coins. Since the fear of loss is a strong human motivator, the fear that “if I don’t come back, I might lose out on some free coins” brings players back every day.

Increasing daily rewards

I am not a fan of simply harnessing slot-machine psychology to win coins – I much prefer mechanisms that give users a sense that they have got something valuable and rare, not just in-game currency. Restaurant City from Playfish does just this, by rewarding players with an increasing number of ingredients if they come back regularly.

While this is part random (the exact ingredients), players can increase their rewards by returning regularly,

Maintenance

The heart of many social games is a maintenance mechanic. Think the crops in Farmville or the rents in Millionaire City.

By using a believable process (like harvesting crops or collecting rents) you build an expectation in your players that they have to plant crops, wait a while and then harvest them.

Games like Mafia Wars turn maintenance on its head: you have scarce energy which takes time to replenish (or you can pay to top it up). It’s the same broad principle of giving players a reason to believe that they have “finished” playing for a while, and should return later, once their crops have grown or their energy has been replenished.

Frontierville combines both. It has a crop-growing mechanic AND an energy mechanic. (Personally, I find the double whammy too much, and find Frontierville close to unplayable as a result. However, it is Zynga’s second most successful game with nearly 30 million according to Appdata, so the combination clearly works for some people.)

Commitment

Commitment is a much more powerful variant of maintenance. The key difference – and this is crucial – is that the player sets when they need to come back.

Let’s take, for example, a harvest mechanic in which all plants take 12 hours to grow. If I plant crops at four in the afternoon during a dull lull at work, I would have to set my alarm for 4am to get out of bed and harvest them. While some extremely committed players might do this, I wouldn’t. What’s more, I am likely to think “bloody stupid game trying to get me to get up in the middle of the night” which is the beginning of the end of my emotional commitment to your game.

Instead, games like Farmville and Millionaire City give the player the choice of when he or she needs to come back. Farmville offers the option of raspberries (which take two hours to grow) and artichokes (which take four days) – and almost everything inbetween. As a player, I can say “it’s a boring day in the office, I can come back in a couple of hours” or “I’m going away this weekend, I’ll plant some crops I can harvest on Monday”.

Not only does it give me flexibility, but because I made a mental and personal commitment to the game – because the timing of when I need to come back seems like it was my decision – the job “harvest crops” goes on my mental to-do list, increasing the likelihood that I actually return.

(Commitment is one of the six key principles of Influence, an outstanding book by psychologist Robert Cialdini. If you are interested in anything I’ve written in this post, you should buy Influence right now.)

Conclusion

Retention is a gameplay issue. It is about changing your design philosophy to keep customers coming back for more, not playing just one more go.

In this post, I’ve focused on Retention for social games. It is just as important for your website (what techniques are you using to make people want to visit your own website? Are you using Facebook, Twitter, email, offers and so on to give people good reasons to return?), for your iPhone title, for your entire portfolio. I will revisit this fractal nature of the ARM framework in a later post.

In the meantime, thinking of interesting ways to encourage users to want to come back will be a very fruitful use of your design energies.